The war against bots

is never-ending, though hopefully it doesn’t end in the Skynet-type scenario we

all secretly expect. In the meantime, it’s more about cutting down on spam, not

knocking down hunter-killers. Still, the machines are getting smarter and

simple facial recognition may not be enough to tell you’re a human. Machines

can make faces now, it seems — but they’re not so good at answering questions

with them.

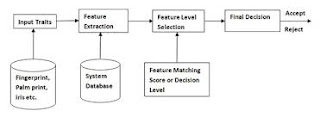

Researchers at Georgia

Tech are working on a CAPTCHA-type system that takes advantage of the fact that

a human can quickly and convincingly answer just about any question, while even

a state of the art facial animation and voice generation systems struggle to

generate a response.

There are a variety of

these types of human/robot differentiation tests out there, which do everything

from test your ability to identify letters, animals and street signs to simply

checking whether you’re already logged into some Google service. But ideally

it’s something easy for humans and hard for computers.

It’s easy for people

to have faces — in fact, it’s positively difficult to not have a face. Yet it’s

a huge amount of work for a computer to render and modify a reasonably realistic

face (we’re assuming the system isn’t fooled by JPEGs).

It’s also easy for a

person to answer a simple question, especially if it’s pointless. Computers,

however, will spin their wheels coming up with a plausible answer to something

like, “do you prefer dogs or cats?” As humans, we understand there’s no right

answer to this question (well, no universally accepted one anyway) and we can

answer immediately. A computer will have to evaluate all kinds of things just

to understand the question, and double-check its answer, then render a face

saying it. That takes time.

The solution being

pursued by Erkam Uzun, Wenke Lee and others at Georgia Tech leverages this. The

prospective logger-in is put on camera — this is assuming people will allow the

CAPTCHA to use it, which is a whole other issue — and presented with a

question. Of course, there may be some secondary obfuscation — distorted

letters and all that — but the content is key, keeping the answer simple enough

for a human to answer quickly but still challenge a computer.

In tests, people

answered within a second on average, while the very best computer efforts

clocked in at six seconds at the very least, and often more. And that’s

assuming the spammer has a high-powered facial rendering engine that knows what

it needs to do. The verification system not only looks at the timing, but

checks the voice and face against the user’s records.

“We looked at the

problem knowing what the attackers would likely do,” explained Georgia Tech

researcher Simon Pak Ho Chung. “Improving image quality is one possible

response, but we wanted to create a whole new game.”

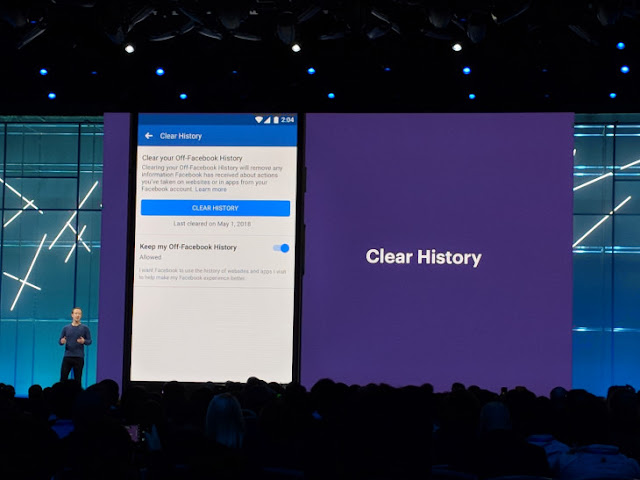

It’s obviously a much

more involved system than the simple CAPTCHAs we encounter now and then on the

web, but the research could lead to stronger login security on social networks

and the like. With spammers and hackers gaining computing power and new

capabilities by the day, we’ll probably need all the help we can get.

No comments:

Post a Comment